What? Am I really blaming poor college research skills on the way we teach middle school research? You bet I am!

In my recent series on common objections to library genrefication, I address the argument that genrefication discourages students from learning to find library resources on their own, which then minimizes their ability to use a university library for research. As part of that series, I wanted to address reasons college students did not get necessary research skills they should have gotten in middle school and high school.

Maybe your school is different. I know some schools are surely better about this than others. But this article is based on my experiences as a middle school librarian in Texas and a Grade 6-12 international school librarian in China.

1. Standardized testing determines EVERYTHING.

At my previous middle school library in Texas, I had a computer lab in the library. Since it was in the library, I was in charge of the daily lab schedule. What I saw, year after year, was that many of our teachers taught their middle school research units after state testing concluded in early May. The computer lab in May would be booked so solid that I frequently had to turn down requests from teachers to book it. In my middle schools, research was more of an add-on instead of a fundamental part of a child’s education.

So why did this happen every year? Well, it wasn’t that the teachers did not want to teach research. The problem was that middle school research skills such as making a bibliography or validating websites, were not tested on the State of Texas Standards of Academic Readiness (STAAR) test. I checked the 2014 released STAAR tests for English I (9th grade), 8th grade science, and 8th grade social studies. Indeed, no questions on any of these tests ask questions about citations, bibliographies, works cited, references, research, or databases.

It takes time to teach middle school research skills and give students the time they need to work with databases in the computer lab. Research skills did not appear on the middle school state tests I checked, but plenty of other concepts did. With the passing of laws like No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top, there is an enormous focus on standardized testing in Texas and other US states. How students perform on standardized tests determines school funding and influences teacher and principal job security. Since there was often not time to teach the concepts that were on the test, middle school research units were frequently put off until after the test, in the last few weeks of school.

Even at the end of the school year, even if a teacher could book the computer lab, their schedule was often interrupted by the STAAR retesting schedule, computer labs needed for “STAAR Boot Camp” (for students who did not pass the STAAR test), end-of-the-year activities, and field trips that were not allowed during testing season. Our entire school year and curriculum revolved around STAAR, which is the number one reason I left the US to teach overseas.

2. Students feel overwhelmed at the amount of information available.

Back when I was in middle school, I had to do a report on a famous person. Since we were also writing a letter to this person, they had to be a currently living person at that time. The teacher arranged this with the librarian, who must have created a list of biographies available in our library. This was in the late-1980s, so we had no access to computers. I had never heard the word “internet,” and more than ten years would pass before I had my own computer.

So using the list of possible famous people, I chose to research Bob Hope. I had one book to research from and possibly an encyclopedia entry. That was it. There was no research database, no Google, no advertisements to muck through. I got all of my Bob Hope information from only two sources.

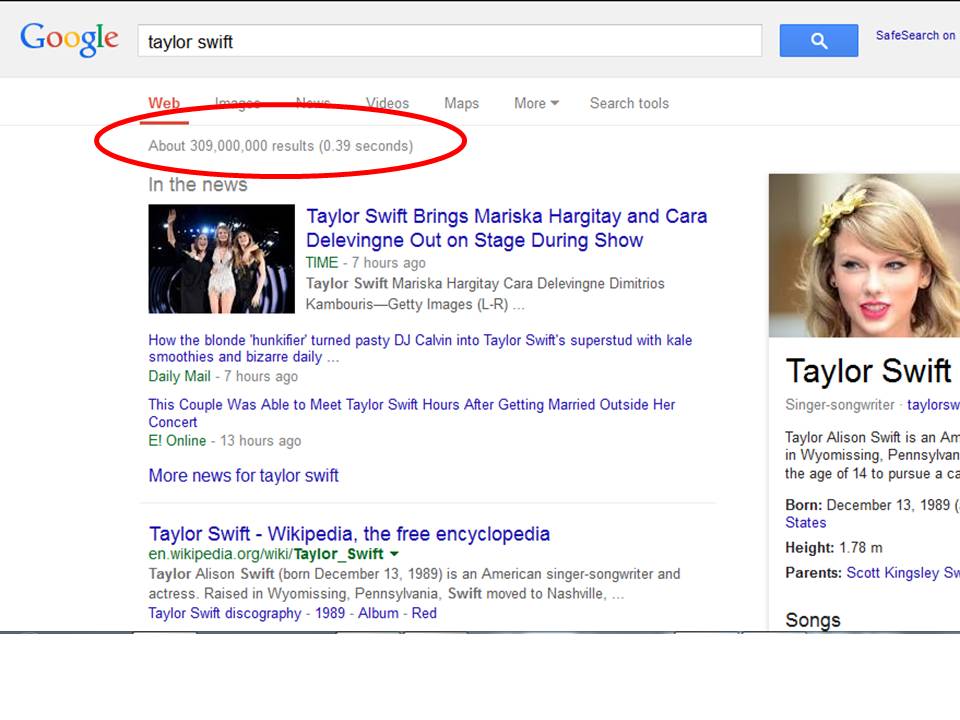

Now imagine today’s 12-year old researching a currently living person. They are no longer limited to available library books, so simply choosing one person to research can be a huge task. Once students have selected their people, they have to start the research process. Naturally, they start with Google. Let’s say that the student is researching Taylor Swift. A Google search of Taylor Swift today nets 309 million results. From 2 to 309 million. A JSTOR search for Taylor Swift returns 28,862 articles. Encyclopedia Britannica returns 409 articles that have something to do with Taylor Swift.

Is it any wonder students have difficulty getting started on a middle school research project?

3. Google and Wikipedia are comfortable and familiar.

In the library computer lab at my previous school, I often heard teachers instructing students to use Google or Wikipedia in their research. Many times, the teachers, like their students, saw these as easier or even better than research databases. Sometimes the teachers themselves do not really understand research databases or how to use them. Students and teachers were already familiar with Google and Wikipedia; they are comfortable and do not require extra instruction (which requires more time).

Very few teachers instructed students on how to evaluate information or validate websites. Some teachers sat and checked email or graded papers while their students researched. In these situations, I often caught students playing computer games instead of researching. I see all this at my current school as well. I don’t say this to bash the teachers I’ve worked with–I’ve worked with so many talented teachers over the years. I say this because it is what I have observed, many times, at more than one school.

But by the end of the year, teachers are exhausted, too. They bring their classes to the computer lab, knowing that students can use Google and Wikipedia without extra instruction. They often don’t consider the fact that most students can’t tell the difference between a valid internet resource and one create by Joe Blow in his mother’s basement. They expect that middle and high school students will know where to begin. They expect students overwhelmed by the amount of information to continue to plug away rather than succumbing to the addictive lure of online gaming. Obviously not.

4. Students are reluctant to ask for help and don’t know what to ask.

Librarians really need to put ourselves out there to make sure students and teachers know we are available to help them. We have to be easy to find (i.e., actually in the library and visible), and we have to show students and teachers that we truly want to help them as often as possible.

When I worked in retail, I discovered that people are more willing to ask for help (and potentially make a purchase) when the salesperson is easy to find, friendly, and offers assistance. The library works the same way: students and teachers who do not know the librarian are less likely to ask the librarian for help. They may not know how to find the librarian. They may perceive, correctly or incorrectly, that the librarian is too busy or reluctant to help.